Your Cavendish memories

We asked our readers to share their recollections of their time at the Cavendish Laboratory, and received tens of submissions, from detailed memories to funny anecdotes (and even a love story). Here is a non- exhaustive selection.

You can read more personal histories on our blog and social media channels.

Caught out!

In 1966, I opted to do Part II Physics which required a Long Vac Term of 8 weekly experiments in the old Cavendish. I soon learned that you only needed

to spend a day or so setting up the experiment and taking preliminary readings. You could look up the result in a text book and invent the rest of the readings, thereby freeing yourself to do what all proper undergrads should do - rowing and partying.

This went well until the final week when I looked up the wrong result and hence invented quite spurious readings.

When I got my write-up back from my supervisor, he had written in red ink a large “See me”. Luckily it was the last day of term and I never had to face the music!

Perhaps this is why I forsook science for a career in finance.

David Ewart-James

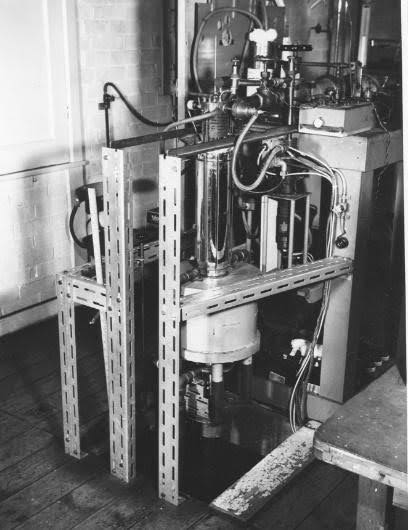

Image: Cryostat for cooling large volumes of superfluid helium below 1 K.

I was a research student in the Royal Society Mond Laboratory within the Cavendish from 1954 to 1957. I had the use of this unique cryostat developed by John Ashmead and Donald Osborne to cool relatively large volumes of superfluid helium below 1 K by adiabatic demagnetisation. At such temperatures, the phonon excitations within the liquid were shown to behave very much like a classical gas with a mean free path comparable to the size of the apparatus. The laboratory had its own helium liquefier and precise measurements were made against the clock by hand- balancing a potentiometer as the helium warmed up. Deliveries of liquid helium and automatic recording instrumentation were not then available.

It was a wonderful experience to be in the Cavendish at this time. We were well aware of developments in things like DNA, protein structure, radio astronomy, electron microscopy and the like but only later did I realise how significant these topics were and what a privilege it had been to be there.

Robert Whitworth

On my very first day, Oct 1988, I was bidden to Head of Administration, a dignified person both in title, and all appearances; fully expecting a lecture

on the importance of adhering to Lab regulations, safety, or some such. Quite contrary, the guy explained to me in some friendly length that the only reason for his existence was to help achieve my scientific goals and, to this end, serve me to the best of his, and his full department’s, abilities. I was quite struck - there sat this Boss of some umpteen people, at least double my age, and told a 4th-year no-grader from abroad that he would do his damnedest to support him, not expecting anything from him. And the key to success is: he meant it!

Christian Naundorf

Cavendish Lab Fall 1988 – as seen from my regular biking approach from St Edmund’s College.

In 1974 I was at Newnham so the move to the new labs meant a less congested bike journey for morning lectures. Lecture rooms were lighter, more comfortable and I suspect most of us were pleased to know there was no mercury under the floorboards!

In my final year the new option of Medical Physics was introduced for the first time and I believe I was the first Cavendish student to undertake my final year project in the subject. The project supervisor was Dr P Dendy and my data on the calibration of the new technique of thermoluminescence dosimetry were used by the medical physics department at Addenbrookes for several years.

The only medical physics jobs available at the time were in Scotland and my Selwyn-physicist fiancé was heading for a teaching job down south. I thus ended up having a few years in biophysics – at one stage using pulsed NMR to study protein- water interactions in an experimental meat substitute now filling supermarket freezers as Quorn.

Another school move resulted in me swapping the very complex biological macromolecules for the relatively simpler synthetic versions and a PhD at Cranfield Institute of Technology (later Cranfield University). My main contribution was to the development of high performance resins for aerospace composites – a field I stayed in for over 30 years, rising through the academic ranks to full professor at the University of Bristol. I may never have understood, let alone remembered, much real physics but the resilience and analytical confidence gained in the years in the Cavendish have been invaluable.

Ivana Partridge

(nee Shott, Newnham 1972)

Every Wednesday we went to the Cavendish for sessions in Brenda Jennison's Physics Education room. Outside was an old desk with a cardboard folded notice saying "This desk belonged to Ernest Rutherford" and every Wednesday we'd all sit on the desk, hoping something would make us better Physicists.

The whole place was full of objects and people like that. Before coming up to Cambridge I had been a government scientist at the National Physical Lab and I had used Josephson junctions to define the volt and every Wednesday Brian Josephson would be sat in the canteen, usually with Sir Neville Mott. It was like being let into a Physics theme park made real.

Steven Chapman

(Postgraduate student, 1993/94)

A brief history of a physicist couple from the Cavendish

Wallace Harper, first left in the second row and Gladys (Mac) Harper, front row second from left at the Cavendish in 1929.

My grandparents, Gladys Isabel Mackenzie Harper (Mac) and Wallace Russell Harper, met and were married while studying in the Cavendish Laboratory in the late 1920s, a time when my grandmother was often the only woman in pictures with dozens of men.

She came from Edinburgh to study at the Cavendish under Professor Lord Rutherford and Dr J. Chadwick with a Newnham College Fellowship and Lectureship. However, she was awarded her PhD by the University of Edinburgh since Cambridge did not confer PhD degrees to women at that time. In 1930 she co-authored a paper with visiting researcher Esther Salaman (G.I. Harper and E. Salaman. 1930. Measurements on the ranges of alpha-particles. Proc. Roy. Soc. A127: 175-185), which might be the first paper in physics co-authored by two women. My grandparents enjoyed cars, dancing, skiing and travelling – they wrote a series of letters about dancing and seeing a Grand Prix car race from a trip to Germany in 1936 just before the war. At that time they were living in Bristol working at Bristol University and had a son (my father, Colin) soon after.

During the war Wallace worked on radar in the Admiralty and Mac apparently ran the Physics Department at the University of Bristol while the men were away at war. Later in her 70s Mac was a part-time lecturer in Physics at Queen Elizabeth College in London. Wallace wrote a couple of textbooks including ‘Contact and Frictional Electrification’, a mystery novel about a murder in a Physics laboratory ‘Scientists Under Suspicion’ and a play about the safety of nuclear energy ‘Not for a Cat’ – to be produced at the 2025 Cambridge Festival!

Karen Harper

Granddaughter and professor in Biology and Environmental Science, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Canada

Wallace Harper, first left in the second row and Gladys (Mac) Harper, front row second from left at the Cavendish in 1929.

My grandparents, Gladys Isabel Mackenzie Harper (Mac) and Wallace Russell Harper, met and were married while studying in the Cavendish Laboratory in the late 1920s, a time when my grandmother was often the only woman in pictures with dozens of men.

She came from Edinburgh to study at the Cavendish under Professor Lord Rutherford and Dr J. Chadwick with a Newnham College Fellowship and Lectureship. However, she was awarded her PhD by the University of Edinburgh since Cambridge did not confer PhD degrees to women at that time. In 1930 she co-authored a paper with visiting researcher Esther Salaman (G.I. Harper and E. Salaman. 1930. Measurements on the ranges of alpha-particles. Proc. Roy. Soc. A127: 175-185), which might be the first paper in physics co-authored by two women. My grandparents enjoyed cars, dancing, skiing and travelling – they wrote a series of letters about dancing and seeing a Grand Prix car race from a trip to Germany in 1936 just before the war. At that time they were living in Bristol working at Bristol University and had a son (my father, Colin) soon after.

During the war Wallace worked on radar in the Admiralty and Mac apparently ran the Physics Department at the University of Bristol while the men were away at war. Later in her 70s Mac was a part-time lecturer in Physics at Queen Elizabeth College in London. Wallace wrote a couple of textbooks including ‘Contact and Frictional Electrification’, a mystery novel about a murder in a Physics laboratory ‘Scientists Under Suspicion’ and a play about the safety of nuclear energy ‘Not for a Cat’ – to be produced at the 2025 Cambridge Festival!

Karen Harper

Granddaughter and professor in Biology and Environmental Science, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Canada

Frozen to the spot

I was a PhD student in the Low Temperature Physics group from 1977 to 1980. To reach temperatures to within a degree of so absolute zero it was necessary to have a double cryostat; the outer containing liquid nitrogen (77K) the inner liquid helium (4.2K). By reducing the pressure above the liquid helium temperatures of around 1.3K could be achieved.

To reach such low temperatures was a slow process. The liquid nitrogen would be added in the morning with the liquid helium following in the late afternoon; the actual experimental data being collected from then until the early hours of the next morning.

After normal working hours, the Cavendish was patrolled by Securicor. One night, I was busy collecting data when I heard a loud, low pitched grrrr. Turning round, I saw an Alsatian at the open door staring directly at me baring its large, sharp teeth and poised to attack. I froze, terrified. After what seemed like an eternity, the handler arrived saying the less than comforting words “Don’t move and you’ll be OK”. Believe me, I had no intention of moving!

Once back on its lead, my heart rate slowly returned to normal and I was able to continue my work but the image of that dog, poised to attack, remains with me to this day.

Keith Gilroy

(Churchill College alumnus)