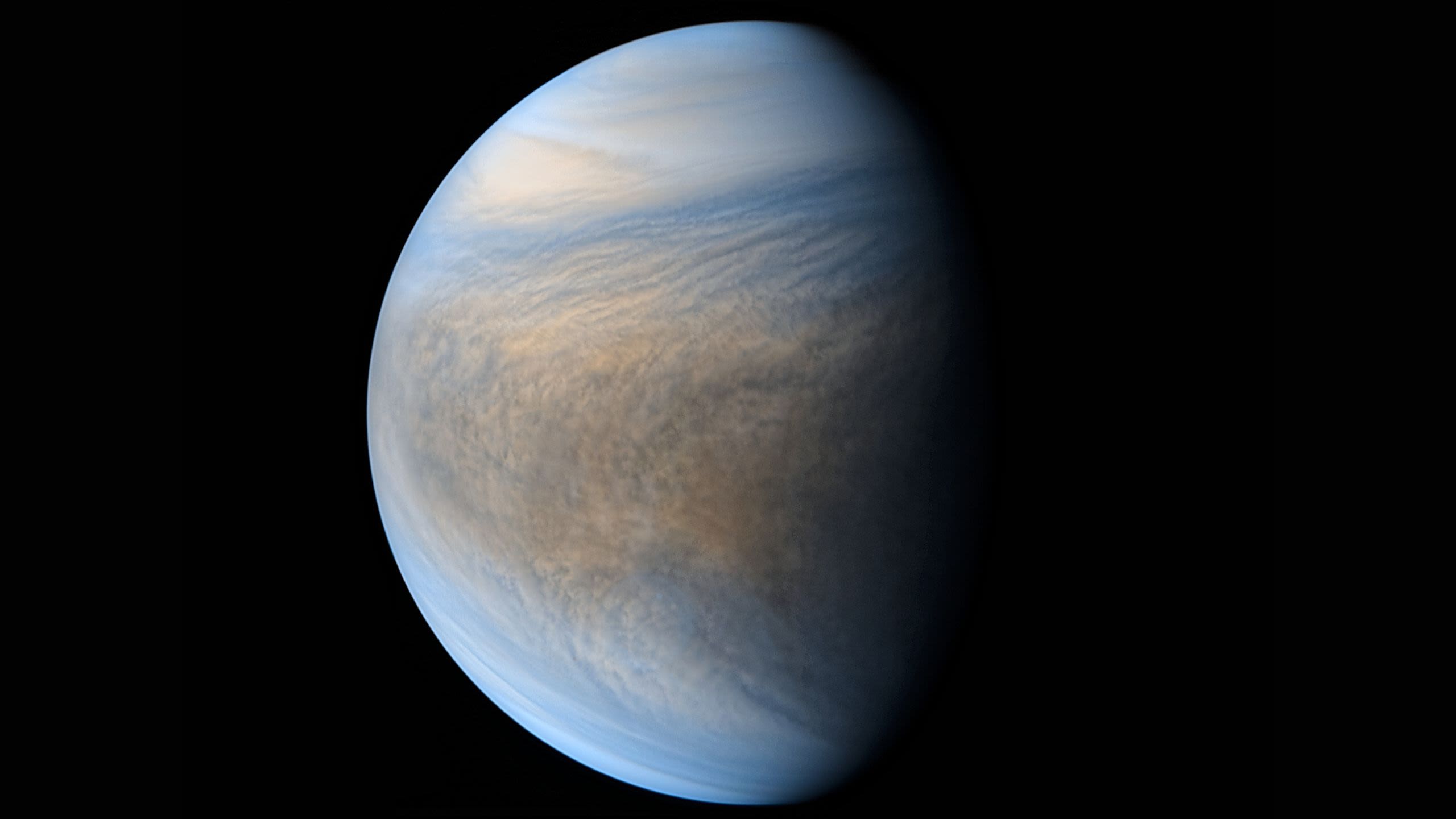

Venus's dark clouds

A team from the Cavendish and the Department of Earth Sciences may have finally solved a hundred-year-old mystery over dark streaks in the atmosphere of Venus.

In optical light, Venus is a bright pale-yellow orb, a featureless pearl suspended in the blackness of space. The planet owes its colour to the scattering of light by its cloud tops, which are made mostly of sulfuric acid droplets, with some water, chlorine, and iron.

But look at the planet in ultraviolet and you discover a series of strange dark streaks and patches that astronomers have, so far, been unable to explain.

These dark patches are collectively referred to as the ‘unknown ultraviolet absorber’. After Soviet and American probes found evidence of iron in the clouds of Venus, Vasilii Moroz, one of the planetary scientists who helped design the Soviet probes, suggested that iron and sulfur might explain the ultraviolet absorber. But until recently, this hypothesis had not been investigated experimentally.

What compounds does iron form when mixed with sulfuric acid and small, but varying amounts of water?

This is the question I started to explore with Clancy Jiang and Nicholas Tosca of Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences. When we first discussed iron-sulfur mineralogy in the clouds of Venus, Jiang and Tosca thought the closest analogy was sulfuric acid drainage in mines here on Earth. Based on minerals found in these mines, we hypothesised that Venus’s clouds may contain a mixture of the iron-sulfur minerals copiapite and rhomboclase, along with acid ferric sulfate.

Reproducing the acidic conditions of Venus’s clouds in the lab, Jiang found that the Venusian atmosphere is far too harsh an environment for copiapite. However, rhomboclase and acid ferric sulfate could form, and Jiang went on to synthesise them.

Taking some of Jiang’s samples, I studied their spectra using an ultraviolet-visible light spectrometer that I built with Samantha Thompson at the Cavendish. I found that the ultraviolet absorption of a combination of rhomboclase and acid ferric sulfate looked a lot like the 350-400 nanometre ultraviolet absorber in the clouds of Venus!

However, the dark patches on Venus also absorb ultraviolet between 250 and 350 nanometres, so what might explain that? Gabriella Lozano, Corinna Kufner and Dimitar Sasselov of Harvard University’s Centre for Astrophysics found that dissolved iron might be the culprit.

So, are we right?

Are the clouds of Venus really peppered with rhomboclase and acid ferric sulfate? Do these compounds finally answer a nearly century-old mystery?

It’s too soon to say. To really know for sure, new probes will have to go to Venus that have the ability to detect minerals in its atmosphere. Our first chance to learn more will come from NASA’s DAVINCI mission, scheduled for launch in 2029, which will study Venus in ultraviolet from orbit while a lander will sample the atmosphere during its descent to the surface.

Clancy Zhijian Jiang et al., 'Iron-sulfur chemistry can explain the ultraviolet absorber in the clouds of Venus.' Sci. Adv. 10, 8826(2024).