Peter Doherty: twenty-five years of innovation

Peter Doherty defines himself both as an instrument maker and a people person. A fan of science fiction, a Star Trek reference is never far from his lips. We sat down to discuss his twenty-five years of service as the Astrophysics Group's Chief Mechanical Workshop Technician.

You started in the Astrophysics Workshop in 1998 after an already long and fruitful career in industry. Tell us how you found your way to the Cavendish.

I did an apprenticeship as an instrument maker before emigrating to Canada, where I worked for the aircraft industry and on nuclear power stations. When I returned to the UK, I joined PYE Telecoms where I spent 12 years before they closed the factory and I had to look for a new job. I came across the job advert almost by accident! After a rigorous interview process (nine hours in three different rounds), I was hired to join the Radio Astronomy Group’s workshop as a technician.

I started on a three-year contract to work on a project called the Heterodyne Array Receiver Project or HARP. I was made permanent after that.

As a technician, I go from fixing a 120 tonnes telescope to machining components with precision up to two microns. Not one day is ever the same as many colleagues often approach me with questions and challenges to solve. This is a very rich and diverse environment to work in.

Did you have any prior interest in radio astronomy or astrophysics before joining the team, or were you simply driven by curiosity?

No, I knew nothing at all about radio astronomy! I remember stumbling upon the Mullard Observatory site when I was 15 and making a joke about aliens. About a year before I started in the role, they had an open day and my wife and I were debating about going in to have a look. We finally decided that we would go another time. That other time turned out to be the following year when I was already working there, and I was the one welcoming people in!

Tell us about the Mullard Observatory at Lord’s Bridge. How was the site when you started and how has it evolved with time?

Originally Lord’s Bridge was just farmland, but since 1957 it’s been the home of huge telescopes. This includes the Ryle of course, with its eight massive 50-ton telescopes, as well as the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (COAST) and the Very Small Array. In more recent years, we have also added the Arcminute MicroKelvin Imager (AMI). AMI is comprised of a small array of ten 3.7-metre telescopes, and a large array of eight 13-metre dishes of the Ryle Telescope, rearranged in a new configuration.

Nowadays, telescopes tend to be built by international collaborations and we don’t do this on our own anymore. However, we continue to build prototypes for bigger projects in other parts of the world, SKA and HERA for example.

The history of the site is so rich, I have made a bit of my speciality to give tours to all kinds of groups, including primary and secondary school children, radio and optical astronomy enthusiasts, and even Cambridge astronomy students. In 15 years, I must have done about 80 tours for more than 1,000 people. This is not officially part of my role, but I have been a happy volunteer ever since my first tour.

"... the overwhelming sense of achievement in that moment was priceless. If only I could capture that feeling and sell it, it would be a treasure beyond measure."

Over the last 25 years, what would you say has been the most rewarding moment?

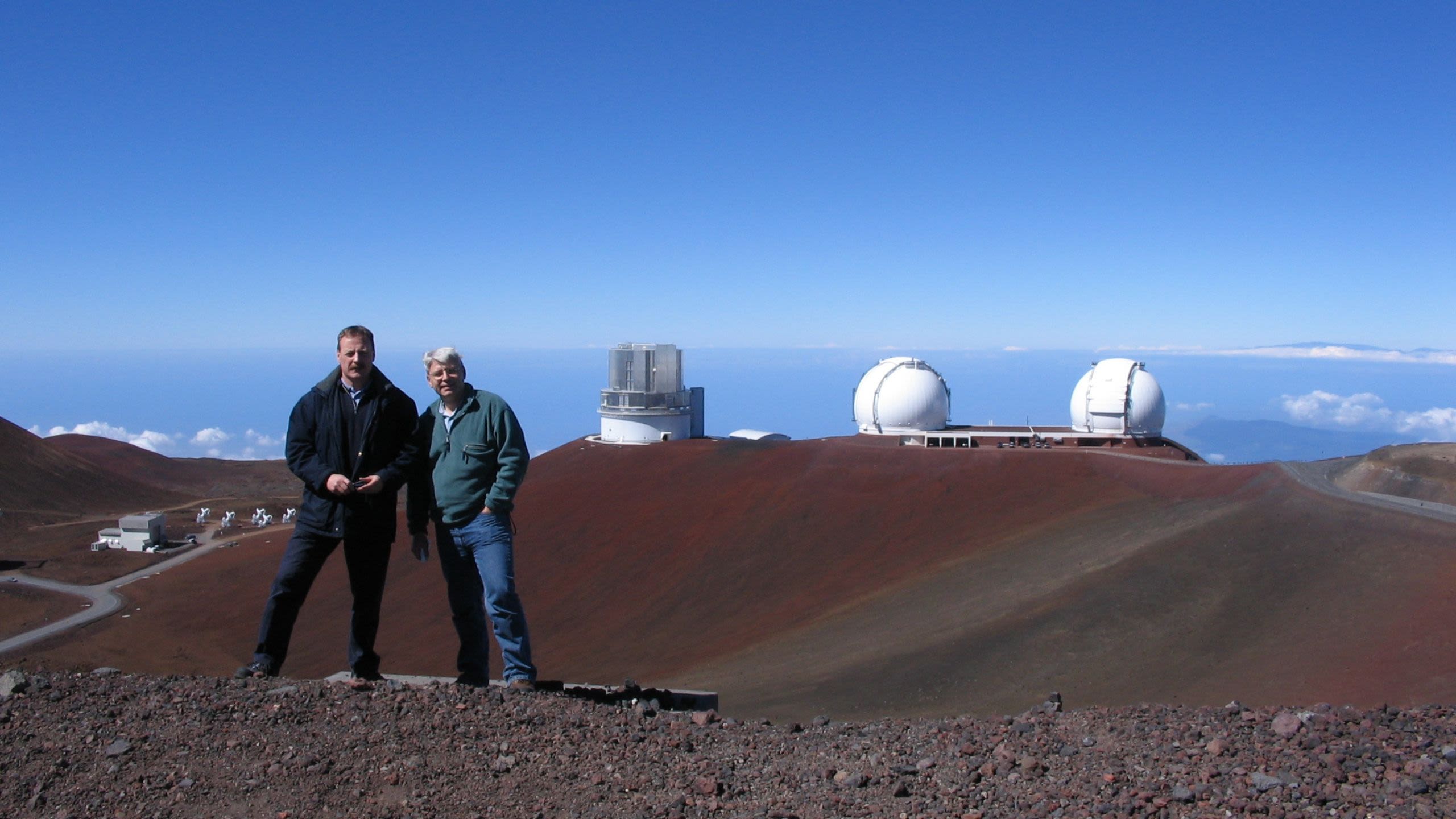

One project that fills me with immense pride is the HARP project. The goal was to create a 350 gigahertz, 16-element receiver for the James Clark Maxwell telescope in Hawaii, with unparalleled accuracy, down to plus or minus two thousandths of a millimetre. It was a daunting challenge as the machines we had were not originally designed for such precision. What made it even more remarkable is that the blocks were never machined that way again.

The process involved assembling circular horns and corrugations to ensure the beam patterns exceeded expectations. After six years of hard work, we successfully assembled the receiver and took it to the telescope in Hawaii. To my delight, it worked flawlessly and to this day, it is still in use and functioning perfectly.

The satisfaction I felt from completing such a highly complex task was indescribable. Witnessing the beam patterns generated from the meticulously machined blocks was incredibly satisfying. All the time and effort put into crafting the blocks, knowing they couldn't be replicated, made the success even more remarkable.

I never truly doubted that it would work, but the overwhelming sense of achievement in that moment was priceless. If only I could capture that feeling and sell it, it would be a treasure beyond measure.

Did you ever think you'd spend half of your career in this role?

I have never felt the need to constantly change jobs. I value building relationships and working with great people as much as the job itself. I have found this at the Cavendish, where I have had the opportunity to excel and contribute to long-term projects from start to finish. This level of involvement and seeing a project through to completion is a dream come true for me as an engineer.

Finally, having a good reputation and being helpful to others has always been important to me. Just like Scottie in Star Trek who didn’t want to become a relic, being useful is the most important thing to me. I'll definitely miss the feeling of knowing I've helped others and created things when I eventually move on from the Cavendish.