Illuminating the Universe’s Dark Ages from the far side of the Moon with CosmoCube

Kaan Artuc

To explore how the first stars emerged from cosmic darkness, Cavendish astronomers are turning their ground-based expertise toward a mission to the far side of the Moon. This satellite will listen for faint radio signals from the Universe’s Dark Ages, offering a rare chance to study the cosmos before the first stars were born.

Hidden behind the Moon, far from the constant buzz of Earth’s radio noise, Cambridge scientists are preparing to detect one of the faintest signals in the Universe—the 21-cm signature from neutral hydrogen that filled space before the first stars were born. The CosmoCube mission, led by the Cavendish Laboratory, aims to capture this ancient signal from lunar orbit, offering a new window into the Universe’s Dark Ages. Supported through two successful funding phases totalling £1.7 million from UKSA, the project has already reached major milestones in design and testing, and now seeks Phase 3 funding to complete its path to launch.

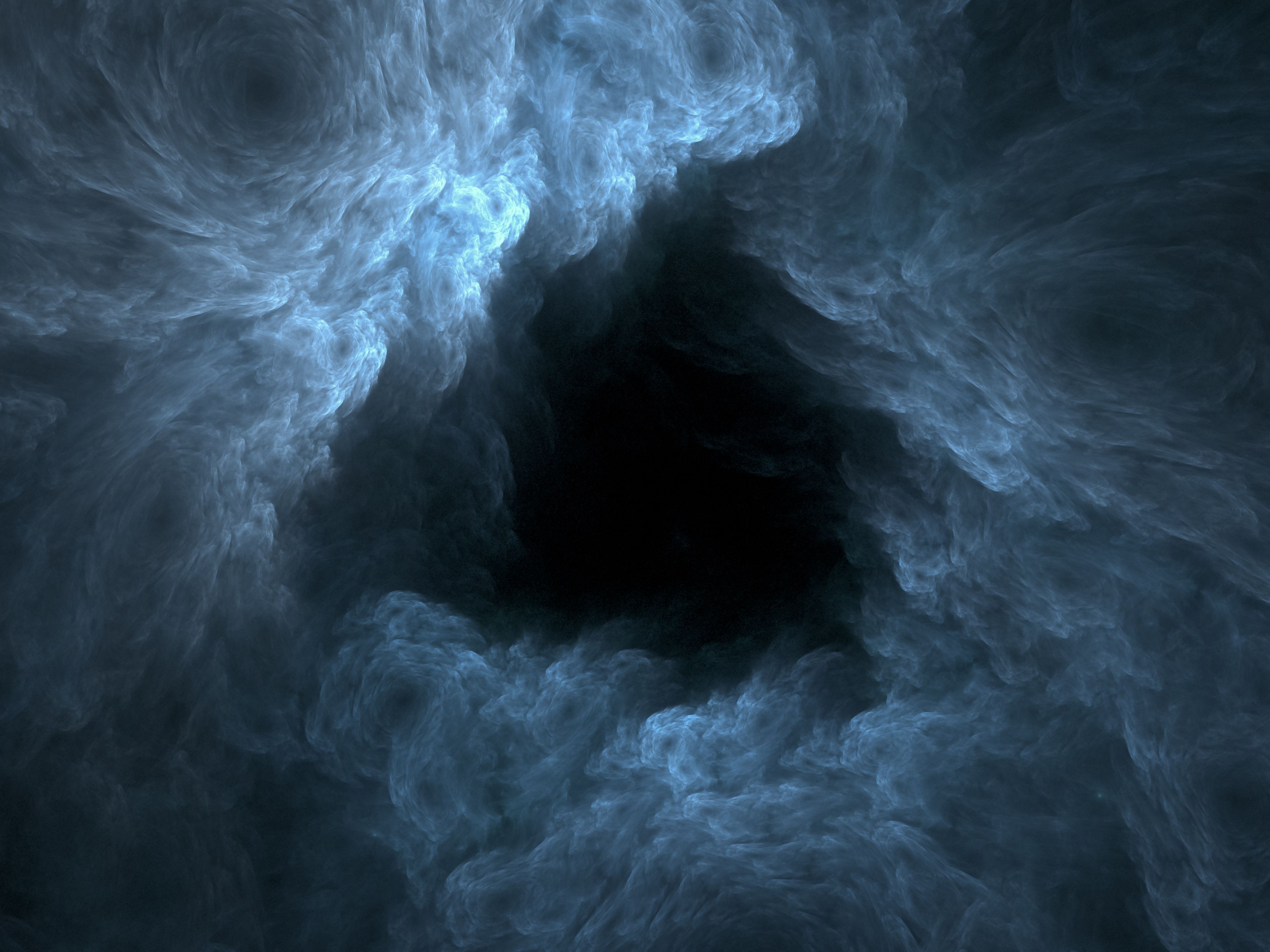

The Dark Ages began about 380,000 years after the Big Bang and lasted until the first stars ignited. During this time, the Universe was filled with neutral hydrogen gas, and its only light was the afterglow of the Big Bang, known as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). As the Universe expanded, this hydrogen produced a faint 21-cm signal, now stretched (or redshifted) into the 5–45 MHz range.

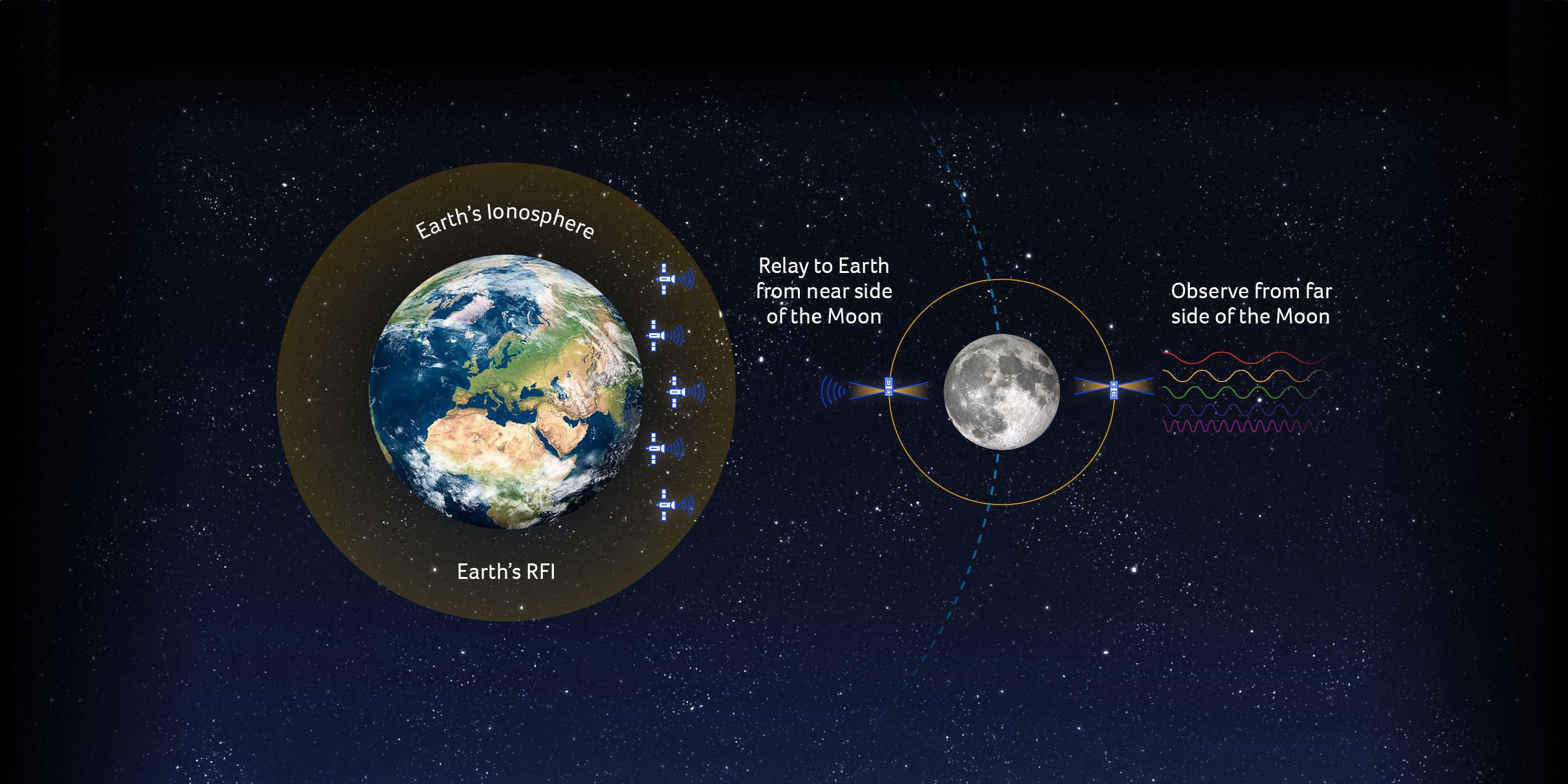

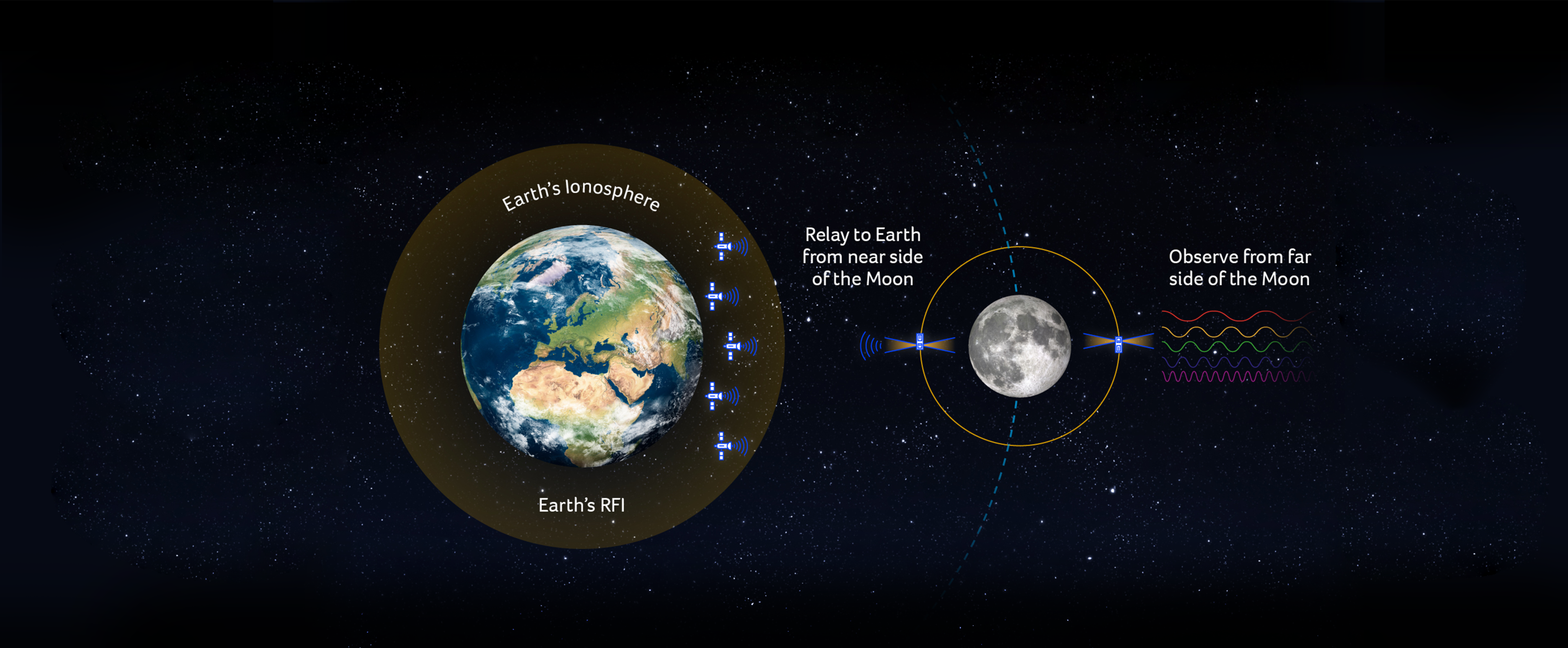

Detecting this faint radio signal offers a direct look at the early Universe’s temperature, density, and the influence of dark matter. It’s a scientific milestone akin to the first detection of the CMB in the 1960s, but vastly more challenging. From Earth, the 21-cm signal from the Dark Ages is completely masked by our ionosphere and human-made radio interference. The solution: take the telescope somewhere truly quiet—the far side of the Moon.

Hidden behind the Moon, far from the constant buzz of Earth’s radio noise, Cambridge scientists are preparing to detect one of the faintest signals in the Universe—the 21-cm signature from neutral hydrogen that filled space before the first stars were born. The CosmoCube mission, led by the Cavendish Laboratory, aims to capture this ancient signal from lunar orbit, offering a new window into the Universe’s Dark Ages. Supported through two successful funding phases totalling £1.7 million from UKSA, the project has already reached major milestones in design and testing, and now seeks Phase 3 funding to complete its path to launch.

The Dark Ages began about 380,000 years after the Big Bang and lasted until the first stars ignited. During this time, the Universe was filled with neutral hydrogen gas, and its only light was the afterglow of the Big Bang, known as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). As the Universe expanded, this hydrogen produced a faint 21-cm signal, now stretched (or redshifted) into the 5–45 MHz range.

Detecting this faint radio signal offers a direct look at the early Universe’s temperature, density, and the influence of dark matter. It’s a scientific milestone akin to the first detection of the CMB in the 1960s, but vastly more challenging. From Earth, the 21-cm signal from the Dark Ages is completely masked by our ionosphere and human-made radio interference. The solution: take the telescope somewhere truly quiet—the far side of the Moon.

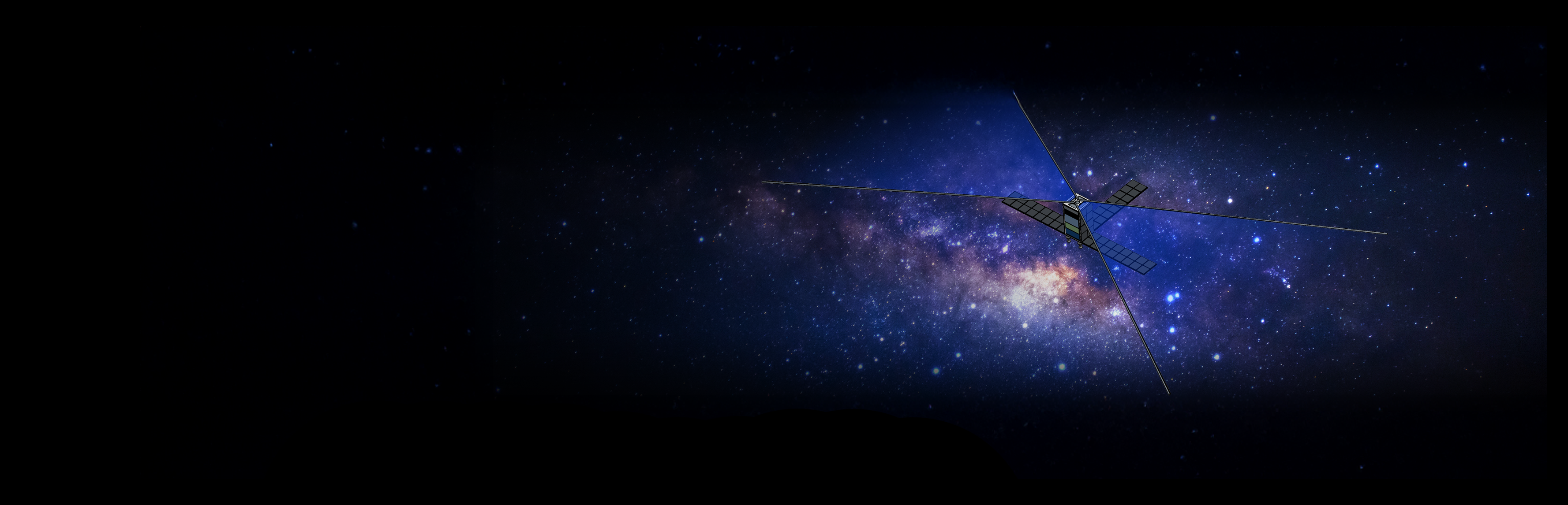

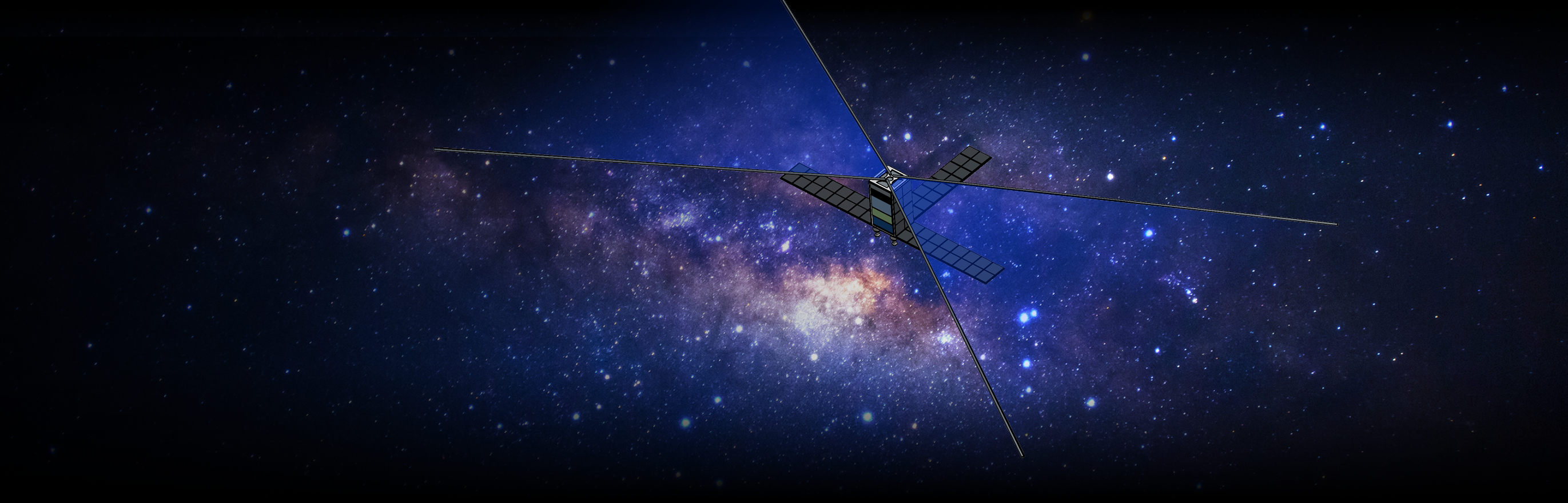

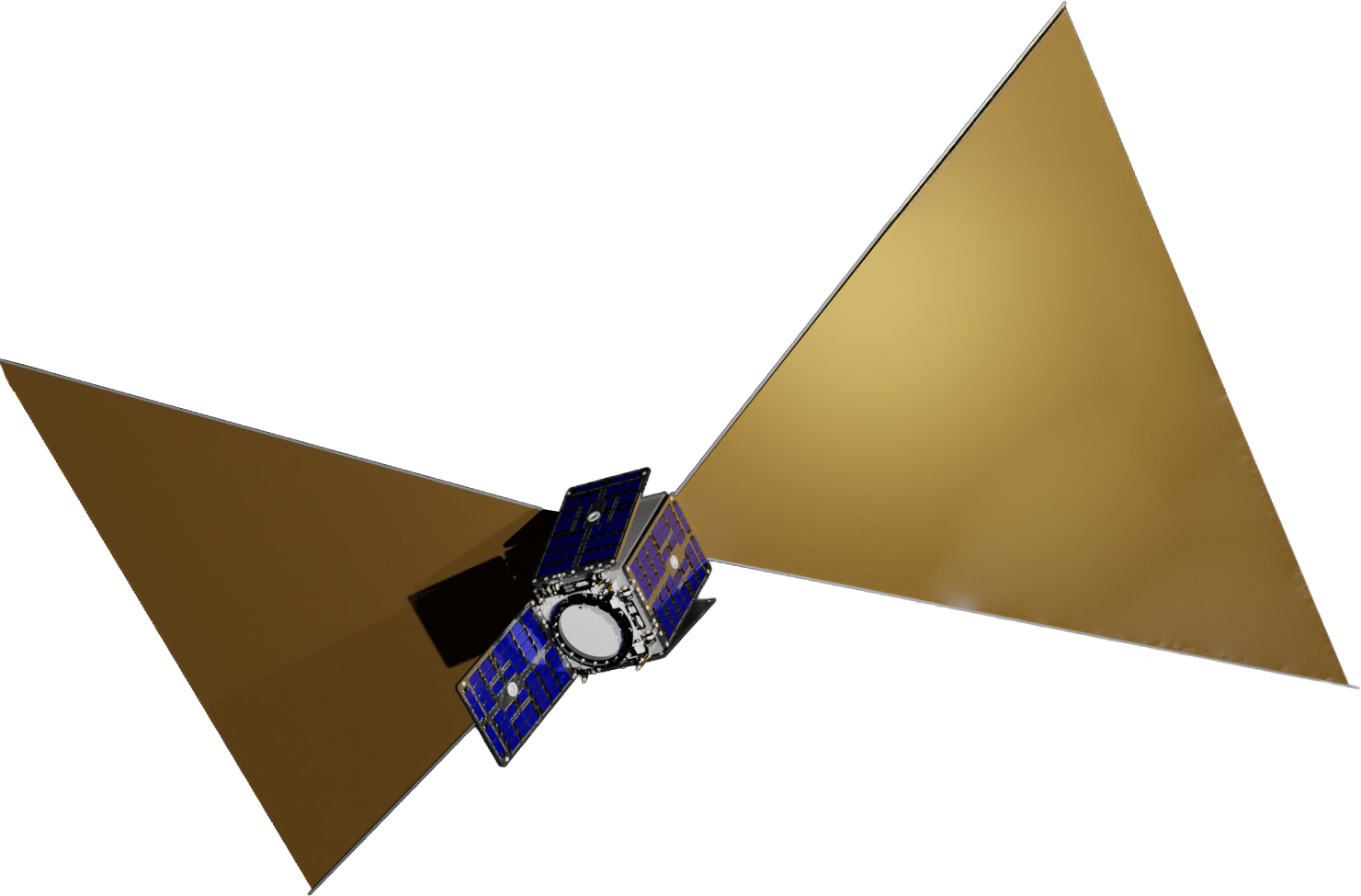

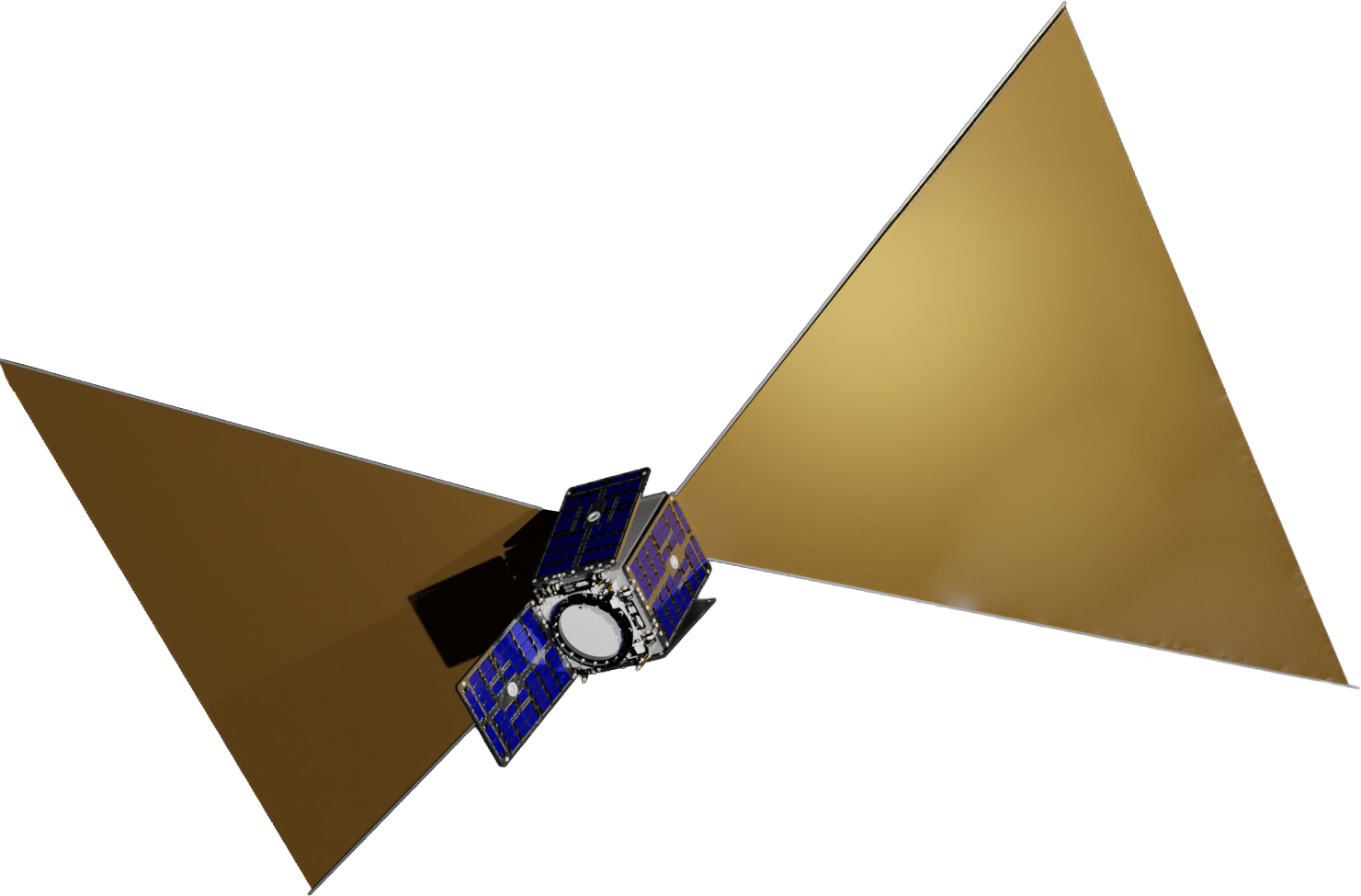

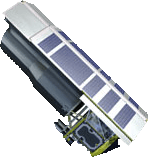

An artist’s impression of CosmoCube orbiting the Moon. Credit: Nicolo Bernardini (SSTL Ltd) & Kaan Artuc (University of Cambridge)

The lunar advantage

The far side of the Moon is a naturally radio-silent zone in the inner Solar System. There, the lunar body itself blocks Earth’s transmissions, creating an occultation where cosmic signals can be heard unspoiled. CosmoCube will orbit this region, spending long stretches of time within the Moon’s radio shadow to observe the untouched radio Universe.

Unlike bulky landers or arrays, CosmoCube is a satellite, roughly the size of a small suitcase. Its compact form hides a sensitive radiometer that measures the brightness of radio waves across a range of frequencies. By tracking tiny temperature variations in these radio emissions, the radiometer reconstructs the global history of hydrogen’s cooling and heating over the first hundred million years after the Big Bang.

The lunar advantage

The far side of the Moon is a naturally radio-silent zone in the inner Solar System. There, the lunar body itself blocks Earth’s transmissions, creating an occultation where cosmic signals can be heard unspoiled. CosmoCube will orbit this region, spending long stretches of time within the Moon’s radio shadow to observe the untouched radio Universe.

Unlike bulky landers or arrays, CosmoCube is a satellite, roughly the size of a small suitcase. Its compact form hides a sensitive radiometer that measures the brightness of radio waves across a range of frequencies. By tracking tiny temperature variations in these radio emissions, the radiometer reconstructs the global history of hydrogen’s cooling and heating over the first hundred million years after the Big Bang.

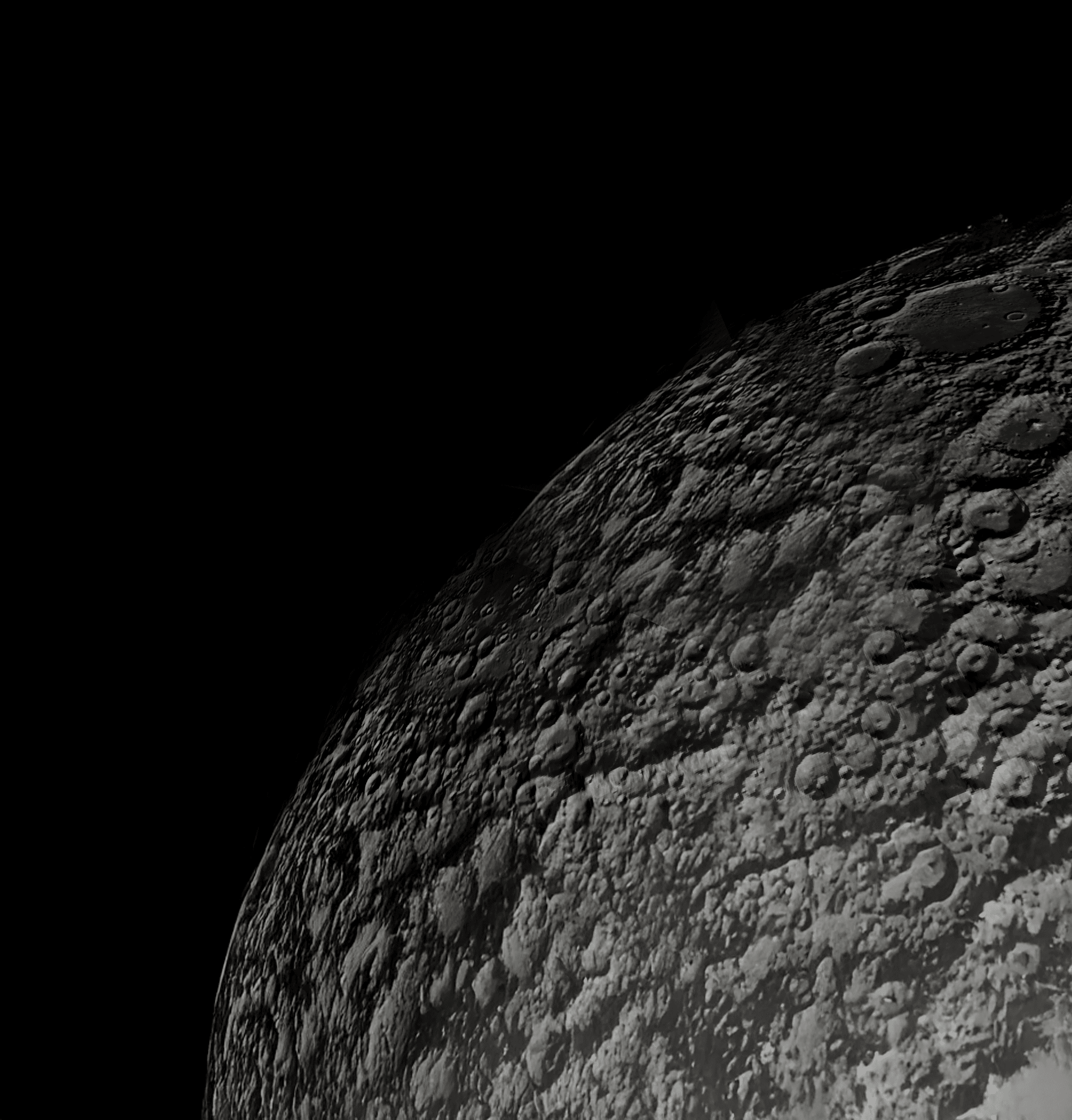

CosmoCube orbiting the Moon.

Science goals

The primary goal is to detect the faint radio glow from hydrogen during the Dark Ages, specifically the all-sky 21-cm features between 5 and 45 MHz. This corresponds to when the cosmos was just 4 to 100 million years old. Measuring the depth and shape of this feature will trace how hydrogen cooled and how the first light sources began to reheat it.

The data will also provide a new way to measure the expansion rate of the Universe, helping to address the long-standing ‘Hubble tension’ between early and late Universe measurements. Furthermore, the observations will test key ideas about dark matter by constraining its interaction with ordinary matter, revealing how cosmic darkness gave way to light and structure.

The Cavendish Laboratory provides scientific leadership, hardware design, and signal-processing expertise, as well as modelling and advanced data analysis frameworks. As a pathfinder, CosmoCube will pave the way for future lunar radio arrays, laying the foundation for a new era of radio cosmology from space.

Science goals

The primary goal is to detect the faint radio glow from hydrogen during the Dark Ages, specifically the all-sky 21-cm features between 5 and 45 MHz. This corresponds to when the cosmos was just 4 to 100 million years old. Measuring the depth and shape of this feature will trace how hydrogen cooled and how the first light sources began to reheat it.

The data will also provide a new way to measure the expansion rate of the Universe, helping to address the long-standing ‘Hubble tension’ between early and late Universe measurements. Furthermore, the observations will test key ideas about dark matter by constraining its interaction with ordinary matter, revealing how cosmic darkness gave way to light and structure.

The Cavendish Laboratory provides scientific leadership, hardware design, and signal-processing expertise, as well as modelling and advanced data analysis frameworks. As a pathfinder, CosmoCube will pave the way for future lunar radio arrays, laying the foundation for a new era of radio cosmology from space.

Engineering the instrument

At CosmoCube’s centre is a highly stable radio spectrometer that listens for faint hydrogen signals from the early Universe. It separates incoming radio waves into thousands of frequency channels, searching for the delicate 21-cm imprint buried beneath brighter cosmic foregrounds. Designed and tested at Cambridge, the instrument stays steady across wide temperature swings, ensuring that tiny variations in its readings reflect the sky, not the hardware. A precise internal calibration system, refined through experience with the REACH experiment, another 21-cm effort led by the Cavendish Laboratory, maintains sensitivity stable to within a few thousandths of a degree, allowing CosmoCube to measure the Universe’s earliest radio whispers with confidence.

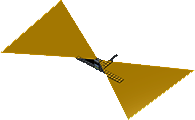

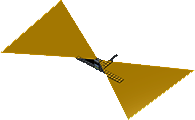

CosmoCube carries a 6-metre deployable bow-tie antenna that stows compactly for launch and unfolds in the orbit of the Moon to capture faint cosmic radio waves. The spacecraft orbits the Moon, spending about 15–20 minutes per lap on the far side. Over the mission’s lifetime, these intervals will total more than 1,000 hours of observation time, enough to detect the Universe’s first hydrogen signal.

Below: Illustration of what CosmoCube will see.

Engineering the instrument

At CosmoCube’s centre is a highly stable radio spectrometer that listens for faint hydrogen signals from the early Universe. It separates incoming radio waves into thousands of frequency channels, searching for the delicate 21-cm imprint buried beneath brighter cosmic foregrounds. Designed and tested at Cambridge, the instrument stays steady across wide temperature swings, ensuring that tiny variations in its readings reflect the sky, not the hardware. A precise internal calibration system, refined through experience with the REACH experiment, another 21-cm effort led by the Cavendish Laboratory, maintains sensitivity stable to within a few thousandths of a degree, allowing CosmoCube to measure the Universe’s earliest radio whispers with confidence.

CosmoCube carries a 6-metre deployable bow-tie antenna that stows compactly for launch and unfolds in the orbit of the Moon to capture faint cosmic radio waves. The spacecraft orbits the Moon, spending about 15–20 minutes per lap on the far side. Over the mission’s lifetime, these intervals will total more than 1,000 hours of observation time, enough to detect the Universe’s first hydrogen signal.

Below: Illustration of what CosmoCube will see.

A race against time

The far side of the Moon may not remain quiet for long. As lunar exploration expands and communication satellites fill its orbit, the pristine radio silence that makes CosmoCube possible could soon vanish. As Dr Eloy de Lera Acedo, the project’s Principal Investigator, puts it:

‘This might be our first and last chance to hear the Universe’s Dark Ages before human noise fills the lunar sky.’

CosmoCube encapsulates the best of Cambridge’s scientific spirit: precision engineering and cosmological ambition. When it launches, it will carry not just a radiometer but a new kind of telescope: one that listens to the Universe’s forgotten ages from the quiet side of the Moon.

A race against time

The far side of the Moon may not remain quiet for long. As lunar exploration expands and communication satellites fill its orbit, the pristine radio silence that makes CosmoCube possible could soon vanish. As Dr Eloy de Lera Acedo, the project’s Principal Investigator, puts it:

‘This might be our first and last chance to hear the Universe’s Dark Ages before human noise fills the lunar sky.’

CosmoCube encapsulates the best of Cambridge’s scientific spirit: precision engineering and cosmological ambition. When it launches, it will carry not just a radiometer but a new kind of telescope: one that listens to the Universe’s forgotten ages from the quiet side of the Moon.

Reference: K. Artuc & E. de Lera Acedo, RAS Techniques and Instruments, 4 (2025).