A tactile

history of

science in

print

Daniel Robins

Physics is communicated in many forms, but perhaps the most enduring is the printed book. For centuries, physicists have filled their shelves with volumes both weird and wonderful, and the bindings, annotations and doodles within those volumes record the lives of the people who leafed through them.

I visited the Whipple Library on Free School Lane - whose staff, Jack Dixon and Liz White, are immensely enthusiastic guides - in search of some of these stories. The collection spans hundreds of years of scientific thought, ranging from a 16th-century astronomy text bound inside an 11th-century manuscript fragment of Genesis, to some books donated to the Cavendish Laboratory from James Clerk Maxwell’s collection. The smallest is a thumbnail-sized edition of Galileo’s letter to Cristina di Lorena. Most striking of all is an unbound copy of Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, its pages still uncut - a 400-year-old book that, almost paradoxically, has never truly been opened.

Image above: Bookplate from one of the volumes donated to the Cavendish from James Clerk Maxwell’s collection.

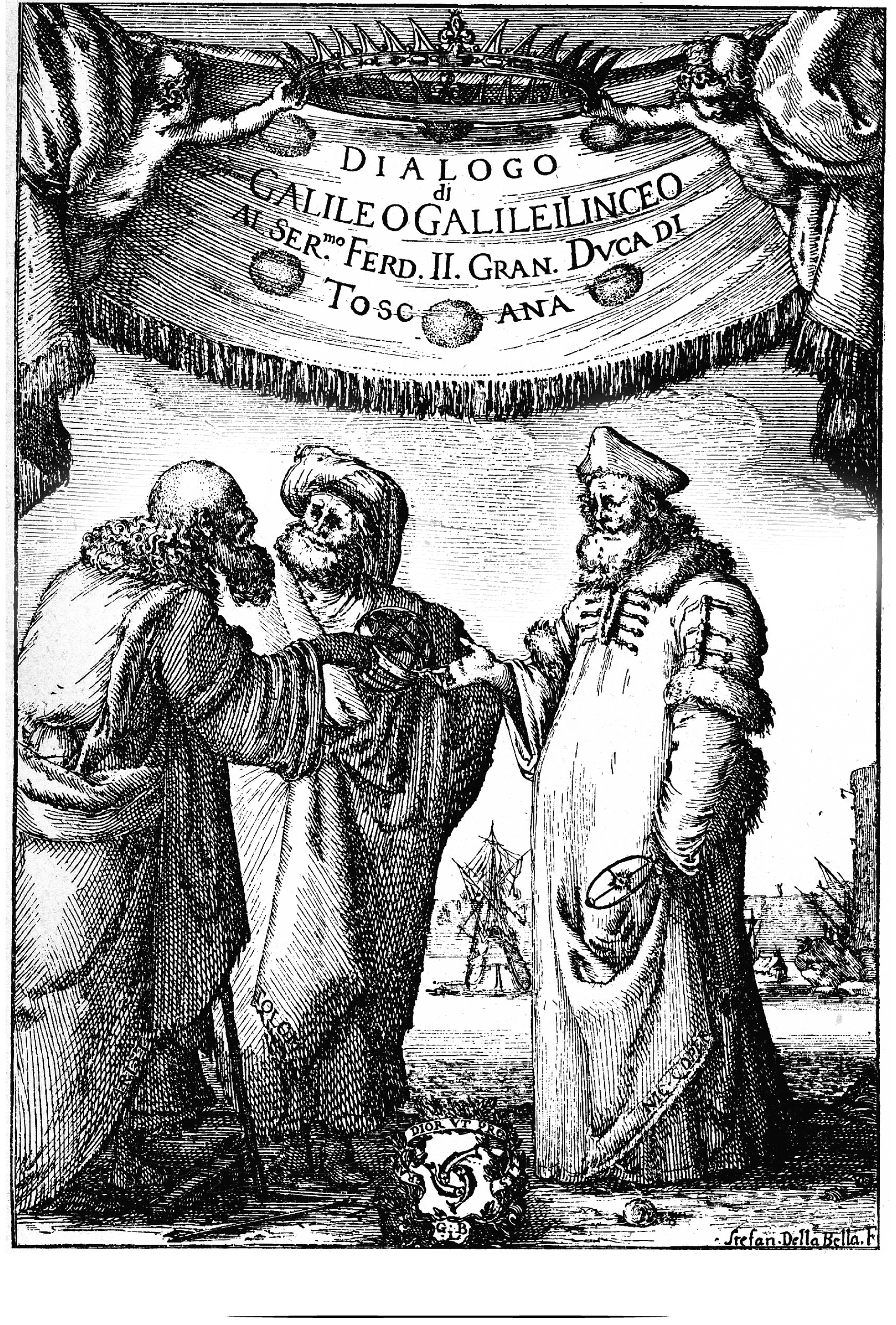

Image right: Dialogo di Galileo Galilei Linceo cover illustration

I visited the Whipple Library on Free School Lane - whose staff, Jack Dixon and Liz White, are immensely enthusiastic guides - in search of some of these stories. The collection spans hundreds of years of scientific thought, ranging from a 16th-century astronomy text bound inside an 11th-century manuscript fragment of Genesis, to some books donated to the Cavendish Laboratory from James Clerk Maxwell’s collection. The smallest is a thumbnail-sized edition of Galileo’s letter to Cristina di Lorena. Most striking of all is an unbound copy of Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, its pages still uncut - a 400-year-old book that, almost paradoxically, has never truly been opened.

Image above: Bookplate from one of the volumes donated to the Cavendish from James Clerk Maxwell’s collection.

Image below: Dialogo di Galileo Galilei Linceo cover illustration

Interactive teaching tools may have exploded in recent years, fuelled by online demonstrations and problem-solving platforms like Isaac Science. Yet many early textbooks were astonishingly tactile too: they had tabs to unfold, and diagrams to rotate, all bound with string. An enduring example is the undergraduate astronomy textbook De Sphaera Mundi by Johannes de Sacrobosco. Originally written in manuscript circa 1230, it was first printed in 1472 and reissued into the 17th century. As such, it survives in both lavish, pristine editions and well-used pocket copies. Its spinning volvelles and tabs were practical tools, designed to be manipulated while answering problems in the text.

Image behind: An example of interactive spinning volvelles in Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera Mundi.

Interactive teaching tools may have exploded in recent years, fuelled by online demonstrations and problem-solving platforms like Isaac Science. Yet many early textbooks were astonishingly tactile too: they had tabs to unfold, and diagrams to rotate, all bound with string. An enduring example is the undergraduate astronomy textbook De Sphaera Mundi by Johannes de Sacrobosco. Originally written in manuscript circa 1230, it was first printed in 1472 and reissued into the 17th century. As such, it survives in both lavish, pristine editions and well-used pocket copies. Its spinning volvelles and tabs were practical tools, designed to be manipulated while answering problems in the text.

Image below: An example of interactive spinning volvelles in Sacrobosco’s De Sphaera Mundi.

When I asked the librarians to choose their favourite books, the first was a wonderfully ambitious attempt at universal order: An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language by John Wilkins, one of the Royal Society’s founders. Wilkins sought to categorise everything in the world and to encode it in a perfectly logical language. One of its curious features (apart from the unexpected four-page discourse on Noah’s Ark inserted in the middle) is that its branching, hierarchical structure looks curiously like a precursor to HTML, albeit published in 1668.

Image left: John Wilkins’ An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language.

When I asked the librarians to choose their favourite books, the first was a wonderfully ambitious attempt at universal order: An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language by John Wilkins, one of the Royal Society’s founders. Wilkins sought to categorise everything in the world and to encode it in a perfectly logical language. One of its curious features (apart from the unexpected four-page discourse on Noah’s Ark inserted in the middle) is that its branching, hierarchical structure looks curiously like a precursor to HTML, albeit published in 1668.

Image above: John Wilkins’ An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language.

A foldout diagram of a comet orbiting the Sun, from Newton’s Principia Mathematica

A foldout diagram of a comet orbiting the Sun, from Newton’s Principia Mathematica

Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

Newton’s Principia Mathematica

Newton’s Principia Mathematica

Another favourite is John Gerard’s Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, annotated by an owner named Anna Pri(n)ce. The book’s marginalia blur the line between science, diary and poetry; before the Enlightenment increased the separation between scientific disciplines, she treated the book as a space for both botanical observation and creative expression. The volume was so culturally significant that several noblewomen had themselves painted with it, alongside the Bible and Ovid.

Image right: The Theory of Sets of Points by Grace Chisholm Young.

Another favourite is John Gerard’s Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, annotated by an owner named Anna Pri(n)ce. The book’s marginalia blur the line between science, diary and poetry; before the Enlightenment increased the separation between scientific disciplines, she treated the book as a space for both botanical observation and creative expression. The volume was so culturally significant that several noblewomen had themselves painted with it, alongside the Bible and Ovid.

Image above: The Theory of Sets of Points by Grace Chisholm Young.

These personal traces - the doodles, the folded diagrams, the pencilled corrections - make each book not just a witness to scientific history, but a participant in it. They invite us to imagine the hands that turned the pages and the lives lived alongside the science. And they leave me wondering: if someone were to leaf through my books, hundreds of years from now, what story would my own scribbles tell about me, and my place in 21st century physics?

For more information about the Whipple Library, visit whipplelib.hps.cam.ac.uk

Or visit, Monday to Friday from 09:15 - 19:00

For more information on the life and works of Grace Chisholm Young, a former Cambridge student, Ruby Gray, has produced an excellent podcast, and given a recent talk, available on YouTube.