Your Cavendish memories

We asked you to share your recollections of your time at the Cavendish Laboratory, and received dozens of submissions, some of which were published in our last issue. Here is a futher non-exhaustive selection.

Fitzwilliam is quite a way from Free School Lane but not so far from the West Cambridge site. After three years commuting through town, the move was very welcome.

In my final year (Experimental and Theoretical Physics), I took Malcolm Longair’s course on “The Origin Of Cosmic Rays”. It was, by a long way, the course I enjoyed most in all three years but, sadly, it was also the shortest being scheduled at the beginning of Finals Term. The quietness of the “New Cavendish” library afforded a rare opportunity in three years of hectic study; to sit back and think. I came up with my “take” on the question Malcolm’s course posed.

When asked, during a supervision, I told Malcolm what my thinking there had led me to. On hearing it, he became very excited and told me “If you write that in the exams, you’ll get a lot of marks”. Curiously enough, the question appeared in the exams so I repeated what I’d said in writing. Equally curiously, not "a lot of marks” seemed to materialise from it as I ended up in the 3rd Class, which ended my hopes of a postgraduate career in radio astronomy at Aberystwyth. It seems, though, that I was destined for the space programme, as my following career led me to being involved in the Rosetta mission in 2014, which saw two landings on solar system bodies.

Leslie Baldwin

(Fitzwilliam, 1971)

I did Natural Sciences from 1964 to 67, in the old Cavendish, and remember the lecture theatre well. I had an awful lot of lectures on those hard wooden benches.

There were 100 of us, and there was only 1 other girl. Some mornings we had 4 hours on the trot in that room, with only a couple of minutes between each. So, we took it in turns to miss one lecture and go for a cup of coffee and then copy someone else's notes. Mind you it was always fascinating, and I remember one lecture where we taught how to build an atomic bomb. The lecturer produced two bits of what he said was Uranium. He put them down 2 feet apart, and then, empty handed, squashed his hands together, saying that if he did this with the Uranium it would get hot and explode. We all cowered back, but ever since I have wondered if this really was Uranium.

I was the first in my family to go to University. My father had a scholarship to Cambridge, but his parents wouldn't let him go! All those drinking parties! So he joined the Post Office and did his degree and Ph.D in the evenings. I always felt that if I could, I ought to do what he hadn't been allowed to.

Virginia Thorne

I was at the end of my research on electron microscopy of irradiated germanium and used to stay at the Lab until very late up to 3 a.m. Alone in such a huge new laboratory, waiting for the preparation of specimens to be used at the microscope, I felt an unforgettable very peculiar sensation difficult to describe. To work at a so distant location was only possible because I had a car. When hungry, I ate biscuits with a glass of water.

Carlos A. Ferreira Lima

(Darwin, 1975)

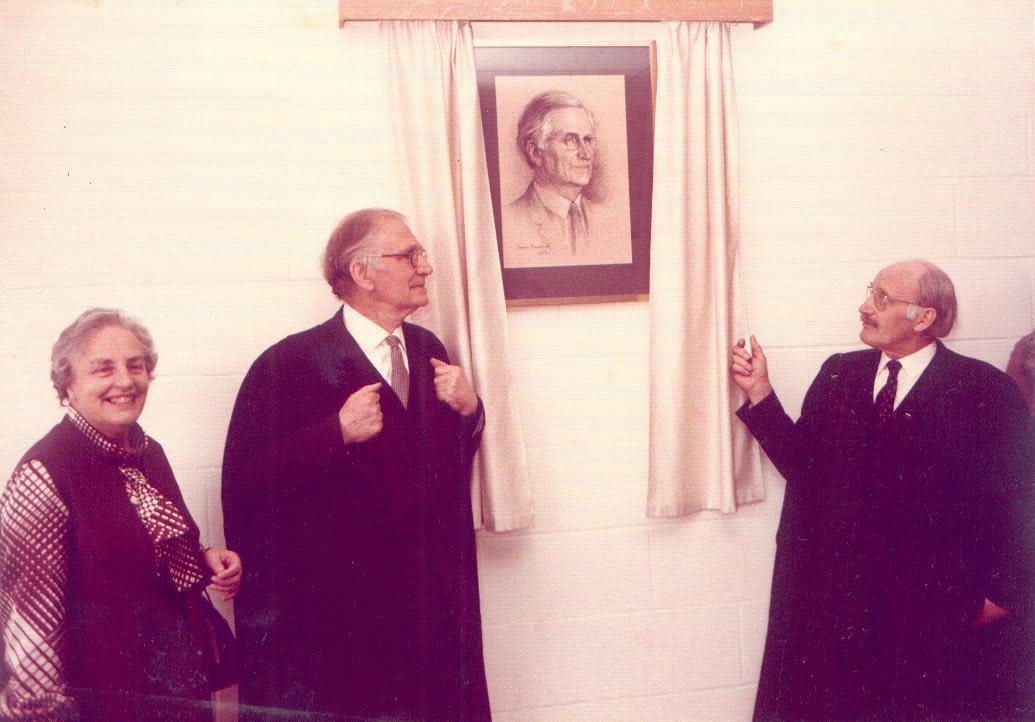

Image: Prof. Sir Neville Mott at the inauguration of his portrait in the new lab.

Image: With colleagues in the New Cavendish. from left to right, Pratibha Gai (now Dame Pratibha), Kamal Hossain, myself and John (surname forgotten).

Shall think of the Cavendish - as so very often I do! Brian Pippard's glorious lectures; the vast kindness of Dr Edward Shire when I had messed up my Finals; and a small roomful of electronics folk in the Austin Wing (one I recall, attempting at that moment, unsuccessfully, to tidy up the table with his wire-cutters) quietly saying to one another, "It simply can't be that fast!" It so happened that it was!

Richard Blackie

Talking about the telescopes during an open day

Talking about the telescopes during an open day

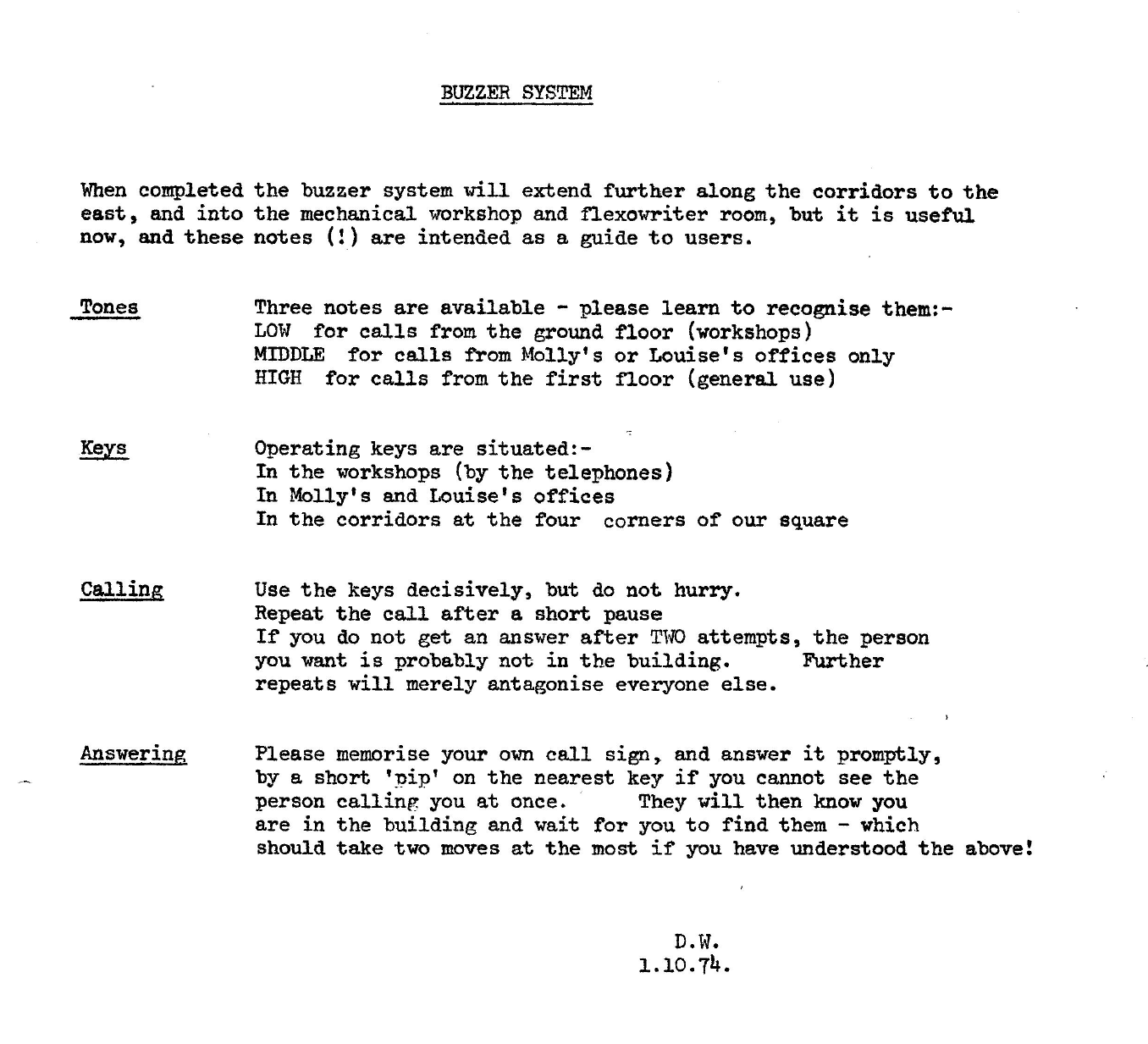

The Radio Astronomy buzzer system user guide and directory – 1974-75

The Radio Astronomy buzzer system user guide and directory – 1974-75

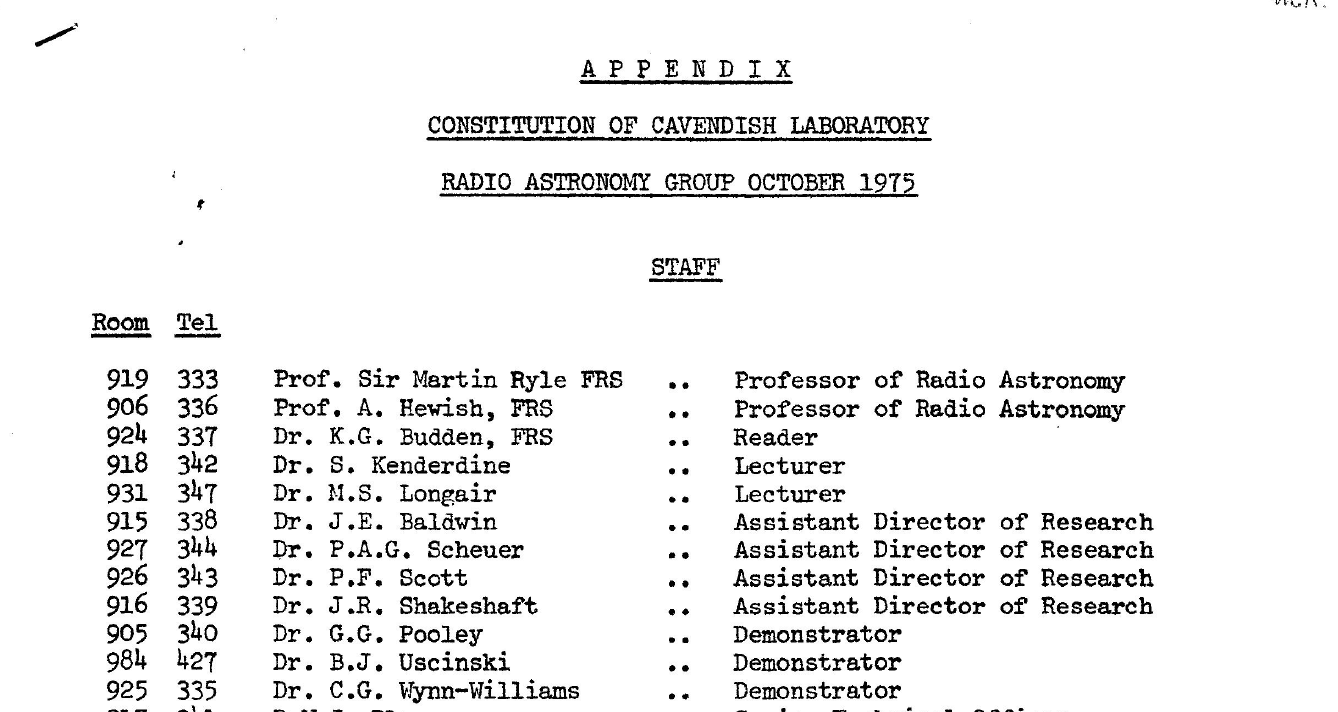

The Radio Astronomy Group 1965

The Radio Astronomy Group 1965

Radio Astronomy Holding Point

I applied to be a doctoral research student at the Cavendish in 1974. I was invited for an interview with Professor Sir Martin Ryle. Feeling nervous, I entered his large corner office on the upper floor and noticed an aeronautical chart laid out on his desk. I had an interest in aviation, and he had worked on airborne radar during World War II. He put me at ease and explained that he was countering a proposal to place a holding point for aircraft over Cambridge; he feared the radio altimeters, etc. would interfere with the radio telescopes. It seems Professor Ryle recognised my knowledge of aeronautical radio systems, and this helped me secure a sought-after place at the Cavendish.

I spent three years at the “new” Rutherford building of the Cavendish Laboratory from 1975 to 1978. I used the Half-Mile Radio Telescope at Lord’s Bridge to observe the outer parts of M33 and several irregular galaxies on the hydrogen line. The Radio Astronomy group in the Cavendish had a unique culture: the checklist for the telescope was “The Co-Pilot’s Guide to the Half-Mile Radio Telescope”; To summon someone in the group, we used a Morse key and transmitted a pre-allocated callsign from a corner of the corridor. If you heard your callsign in a mid-tone, you went to the key; but if the tone was high, it meant go to Martin’s office, and if the tone was low, it meant go outside the engineering labs on the ground floor. There was a special call summoning for coffee in the morning, and tea in the afternoon, where interesting technical discussions took place. The radio telescopes at Lord’s Bridge had the same Morse keys. We sometimes used an old moped with a rusty fuel tank to get there, and my Ford Cortina was thoroughly checked to ensure it did not produce interference. There was a WW2 Würzburg radar dish to help triangulate terrestrial interference, possibly from a sparky washing machine in a nearby village. There is no holding point above the radio telescopes.

Michael Reakes

(Radio Astronomy group, 1975-78)