Building the new

Cavendish Museum

Since the mid 20th century, the Cavendish Laboratory has held a collection of scientific instruments and archival material that embodies the extraordinary history of the laboratory. A beautifully designed new Cavendish Museum has just opened in the Ray Dolby Centre.

By Harry Cliff

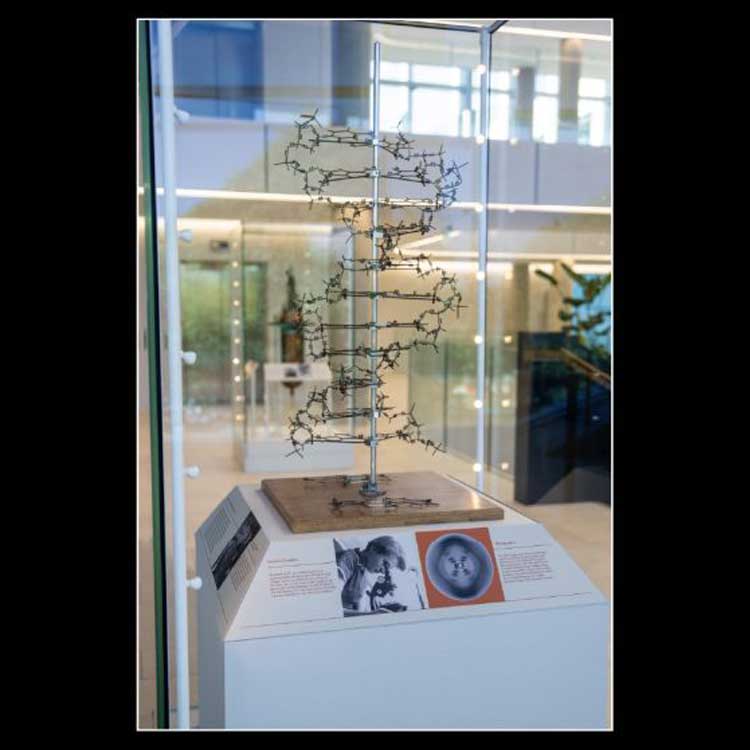

Image: Model of the double helix structure of DNA.

Building the new Cavendish Museum

Since the mid 20th century, the Cavendish Laboratory has held a collection of scientific instruments and archival material that embodies the extraordinary history of the laboratory. A beautifully designed new Cavendish Museum has just opened in the Ray Dolby Centre.

By Harry Cliff

Image: Model of the double helix structure of DNA.

As an undergraduate, I would often stop to gawk at some of the extraordinary scientific instruments on display in the Cavendish Museum, housed on a long corridor on the first floor of the Bragg Building. In a short stretch of cabinets, you could find the cathode ray tube used to discover the electron, Wilson’s cloud chamber that first made the tracks of subatomic particles visible and the small brass tube that Chadwick used to discover the neutron.

These remarkable items are all part of the Cavendish Collection, which was first assembled after the Second World War when Lawrence Bragg, then Cavendish Professor, put out a request for important items that might be hidden in various corners of the laboratory on Free School Lane. Since then, the collection has grown in fits and starts, as new items from the postwar history of the laboratory were added to the display over the subsequent decades.

It is no exaggeration to say that this is one of the most significant collections of scientific apparatus anywhere in the world, especially when it comes to the history of physics in the 19th and 20th centuries. This point became even clearer to me after working with historic collections during my seven-year spell as a half-time exhibition curator at the Science Museum in London.

Now, the Cavendish Museum has been redisplayed in the stunning setting of the Ray Dolby Centre. Last year, I had the privilege of taking on responsibility for the collection from Malcolm Longair, who has spent many years preserving, researching, cataloguing and enhancing the collection. As the new curator, I faced the exciting, if slightly daunting task of creating a display fit for the Cavendish Laboratory’s new home, which unlike the previous museum would be open to the public without appointment, five days a week.

Early on, the Department took the decision to provide a significant budget for the new exhibition. As Mete Atatüre put it, you don’t want to scrimp on something that is relatively cheap (at least compared to the Ray Dolby Centre) and very visible (located in the public wing). This enabled us to appoint an experienced team of museum professionals, supported by a number of university staff, who all gave their time generously to bring the new display into being.

After inviting several design firms to interview, we appointed London architecture studio Drinkall Dean, who have worked extensively with national institutions, including the British Museum, the Science Museum and the V&A. Lead designer Angela Drinkall put together a multi-talented team including graphic designer Helen Lyon from Studio HB, and Clay Interactive, specialists in digital and interactive museum displays.

The design they produced was crisp and modern, with showcases in white powder coated steel and crystal clear low-iron glass, that almost disappear and draw the eye to the objects. The showcases themselves were manufactured by Yorkshire-based company Glasshaus, whose installation team worked tirelessly for four weeks in the Ray Dolby Centre to assemble the showcases and plinths.

A display of historic apparatus in the Austin Wing of the original Cavendish Laboratory on Free School Lane

A display of historic apparatus in the Austin Wing of the original Cavendish Laboratory on Free School Lane

The Ray Dolby showcase, positioned in front of a large sculpture inspired by the circuitry from the Spectral Recording system, Dolby’s final analogue invention

The Ray Dolby showcase, positioned in front of a large sculpture inspired by the circuitry from the Spectral Recording system, Dolby’s final analogue invention

Completed ahead of the official opening of the Ray Dolby Centre on the 9th May, the museum includes six large free-standing showcases that focus on specific discoveries, instruments or people, five interactive touchscreens with reams of deeper content, three plinths displaying some of the larger objects from the Cavendish Collection and two monumental wall cases, which explore themes from the Cavendish Laboratory’s research. These are spread throughout the public wing of the Ray Dolby Centre, with the majority on the first and ground floors.

The first thing you see when entering the building is a showcase dedicated to the life and work of Ray Dolby. Among the items donated by the Dolby family are his original unbound PhD dissertation on X-ray microanalysis at the Cavendish Laboratory, and several iterations of the noise reduction technology he invented at Dolby Laboratories. Complementing these more technical items are pieces that speak to his love of music, which inspired his work on noise reduction, including his clarinet and sheet music. Suspended above the case is a Star Wars movie poster, which was one of the first feature films to use Dolby noise reduction.

The case also features a built-in touchscreen with an interactive timeline of Ray Dolby’s life, researched and written by Cavendish astrophysicist, Charlie Walker and designed by Clay Interactive. The piece incorporates a number of film and audio recordings, including interviews with Ray and an early guitar demo of the noise reduction system that Dolby Labs used to promote their technology to music studios in the 1960s. One particularly touching moment during the official opening of the Ray Dolby Centre was when one of Dolby’s grandchildren told her grandmother that listening to the interview with Ray was the first time she had heard her grandfather’s voice. He had died the year she was born, in 2013.

Image: Dagmar Dolby, wife of Ray, listening to an audio recording in the exhibition at the Ray Dolby Centre official opening

Image: Kaptisa’s helium liquefier on display in the Ray Dolby Centre

Walking further into the public wing you encounter two large tank cases, one containing the iconic DNA model made by the MRC laboratory shortly after Crick and Watson determined the structure of DNA in 1953. The other contains a helium liquefier invented by Pyotr Kapista to supply the Cavendish with liquid helium in the 1930s.

Image: Former Head of Department and Collection Curator, Malcolm Longair and Sean Geraghty with Maxwell’s viscosity of gases experiment

Image: A section of the large wall cases, displaying objects from X-ray crystallography, electron microscopy and low temperature physics

Around the corner is the largest collection of objects in the exhibition, two huge wall cases running the length of the corridor that passes behind the stage of the Ray Dolby Auditorium. These are subdivided into themes, the first telling the story of the origins of the Cavendish Laboratory in the late 19th century, including a section of the first transatlantic cable, an innovation that demonstrated the utility of physics to industry. Nearby, you will find a plinth with the famous experiment that James Clerk Maxwell, the first Cavendish Professor, used to measure the viscosity of gases, which was carefully restored by Sean Geraghty from the workshops team.

Also in this area of the museum is a large wall-mounted touchscreen that allows visitors to browse through the extensive photographic archive, including over a century of annual research student photographs, and countless other images of scientific equipment, laboratory life and lesser-known figures from the Cavendish’s history. High energy physics PhD student Ella Wood did a huge amount of work for this screen, researching and writing pages of material about some of the less well known Cavendish scientists and technicians, many of them women, who contributed enormously to its success.

The photo archive touchscreen and bust of James Clerk Maxwell at the start of the main museum displays

The photo archive touchscreen and bust of James Clerk Maxwell at the start of the main museum displays

Within these cases you can find items that speak to the Cavendish’s pioneering work in nuclear physics, X-ray crystallography, electron microscopy, low temperature physics and astrophysics. Highlights include part of the accelerator built by Cockcroft and Walton in 1930 in their quest to split the atom, Lawrence Bragg’s original X-ray spectrometer and Brian Pippard’s model of the Fermi surface of copper. At the end of the corridor is another freestanding case that explores the observation of pulsars by Tony Hewish and Jocelyn Bell, including Hewish’s pulsar model and another interactive touchscreen with a timeline of the months leading up to their momentous discovery.

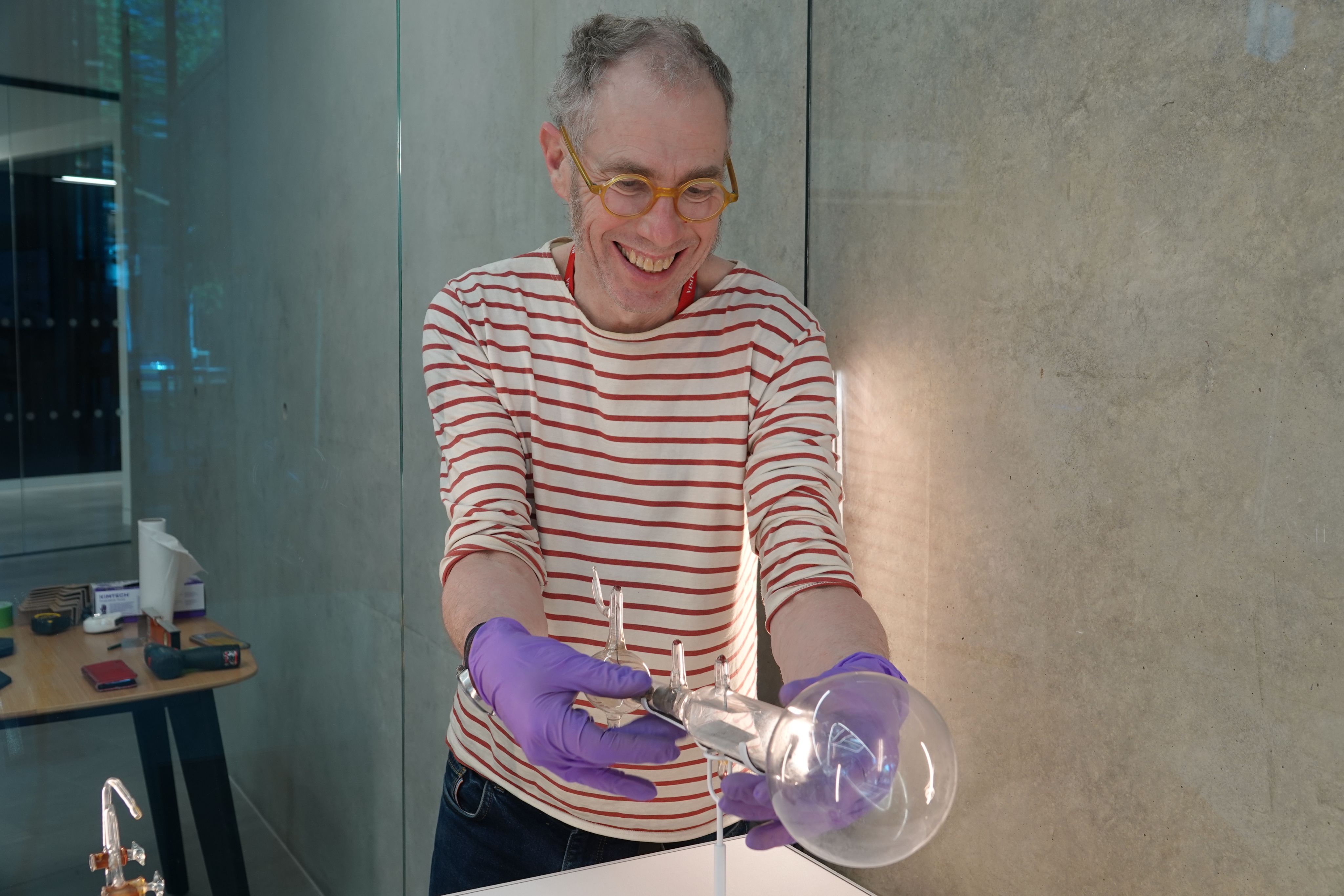

Many of the objects in the museum were sympathetically and delicately mounted by expert museum mount maker Colin John Lindley, who spent several days in Cambridge in total; first measuring and examining each object before they were moved to the Ray Dolby Centre and then returning at the end of April with his handmade mounts to install each object individually. Working with Colin and his colleague and partner Kate Silverston over several days as we installed the collection was a real joy.

Colin John Lindley carefully installing Thomson’s e/m tube in the ‘Atom’ showcase on the ground floor of the Ray Dolby Centre.

Colin John Lindley carefully installing Thomson’s e/m tube in the ‘Atom’ showcase on the ground floor of the Ray Dolby Centre.

The Atom showcase, containing instruments used in the discovery of the electron, proton and neutron. An interactive touchscreen explores the wider contributions of Cavendish researchers to understanding the structure of the atom.

The Atom showcase, containing instruments used in the discovery of the electron, proton and neutron. An interactive touchscreen explores the wider contributions of Cavendish researchers to understanding the structure of the atom.

A particularly nervous moment came when we mounted one of J. J. Thomson’s original cathode ray tubes, used in the discovery of the electron in 1897. The delicate glass tube has not been on display for over a decade, as it was deemed too valuable and fragile for the aged wooden cabinets in the old museum. Now it can be viewed in a single showcase exploring the Cavendish’s contribution to understanding the inner structure of the atom, alongside a later version of Rutherford’s Manchester experiment that discovered the proton, and Chadwick’s neutron discovery experiment, which have also not been displayed for over two decades. It is truly remarkable to find instruments that contributed to the discovery of all three of the subatomic components of the atom in a single case, at a single laboratory.

It has been exciting to see staff, students and visitors pause to engage with the displays over the past few weeks. One of the unexpected consequences of the Museum appearing in the public wing is that it has given the building an identity. Beautiful as the Ray Dolby Centre is, it is not immediately obvious on entering that you are in a laboratory. You might equally be in an elegant corporate office. But as soon as you see the double helix of DNA you can be in no doubt that you are in a scientific building, and more still, the Cavendish Laboratory, reborn for the 21st century. In the coming months and years, we plan to augment these displays with new objects reflecting the Cavendish’s cutting-edge research, so that the Museum becomes a living representation of the laboratory’s past, present and future.

I’d like to finish by thanking the many people who I have had the pleasure to work with on this project, which has occupied larger and smaller parts of many people’s working lives for the past year. I’m particularly grateful to Angela Drinkall for marshalling the team so effectively, to Helen Lyon for her dedication to producing the highest quality graphics and to Adrian Ward for delivering beautiful new digital content right up to the line as we laid the tracks in front of the train. Special mention also goes to David Hunt and Debbie Carminati, who provided invaluable project management support throughout, at a time when they were also extremely busy with the move into the Ray Dolby Centre itself. The new Cavendish Museum is the result of this collective effort.

I hope, in the coming months, you will drop in to explore these remarkable objects, displayed afresh in the Cavendish Laboratory’s new home.

The Cavendish Museum is open to the public without appointment in the Ray Dolby Centre, Monday to Friday, 8am to 5pm.